In a new study, published in Nature Ecology & Evolution, researchers found that non-CG DNA methylation, an epigenetic control system found abundantly in human brains, first made an appearance in the earliest vertebrate animals.

Non-CG methylation has the ability to switch on and off the DNA of genes controlling aspects of the brain’s functioning. The discovery, that non-CG methylation is found across vertebrate animals, suggests that is has played a crucial role in enabling the sophisticated cognitive abilities found in human and other vertebrate brains today.

Professor Ryan Lister, from UWA’s School of Molecular Sciences, who co-led the study, said researchers analysed the brain samples of animals from across the tree of life.

“We wanted to determine if non-CG methylation is restricted to mammalian species, which possess highly complex cognitive abilities, or if it had deeper evolutionary origins,” Professor Lister said.

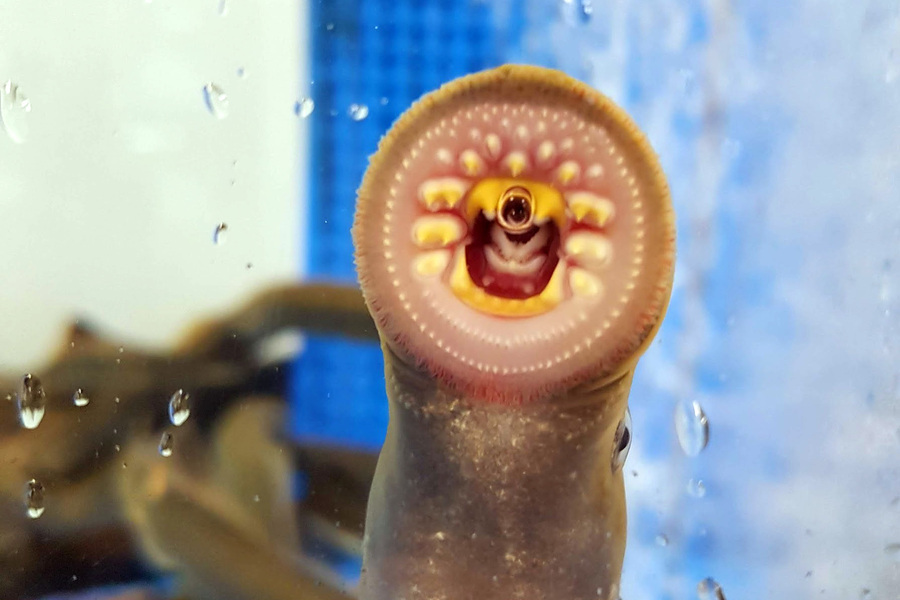

The researchers found that non-CG methylation is seen exclusively in vertebrate animals. This includes lampreys, animals which come from a lineage of ancient, jawless fish that share a common ancestor with humans.

This finding suggests that non-CG methylation arose in the earliest common ancestors of all vertebrates, organisms that roamed the earth hundreds of millions of years ago.

Co-researcher Dr Alex de Mendoza said that this result means that non-CG methylation may have played a crucial role in developing sophistication of the brain.

“We looked for non-CG methylation in the brains of everything we could get our hands on, from marsupials, platypuses, birds, frogs, fishes, sharks, and lampreys, which represents the full range of animals with a spine. We also looked at the brains of several invertebrates such as a honeybee and an octopus,” said Dr de Mendoza.

“We found non-CG methylation evolved at the origin of vertebrates and thus may have been an important requirement for the brain to develop more complex functions.”

The study also revealed that the evolution of all the genetic “tools” required for cells to use non-CG methylation took place at around the same time.

The gene responsible for “writing” non-CG methylation, DNMT3A, and the gene responsible for “reading” it, MeCP2, were found to have originated at the onset of vertebrate evolution.

“This study highlights how events that took place in our fish-like ancestors still play a central role in our own brain biology,” Professor Lister said.

The study was led by Professor Ryan Lister and Dr Alex de Mendoza at the UWA School of Molecular Sciences, the ARC Centre of Excellence in Plant Energy Biology, and the Harry Perkins Institute of Medical Research. Dr de Mendoza now researches at Queen Mary University of London. This study was performed in collaboration with researchers from organisations around the world, including from Spain, France, Singapore, Adelaide and Chicago.