Article authored by Plant Energy Biologist Dr James Lloyd for the Curious Meerkat science blog. Read article in full here.

Genetically modified organisms (GMOs), especially plants, get a lot of hate. People – even some very environmentally conscious people – seem to fear or hate GM crops. Yet, as someone who is very worried about climate change, very worried about the human-induced mass extinction event that is happening before our eyes, and worried about the livelihoods of farmers and about those people that have so little food they go to bed hungry every night, I see GM crops as part of the solution, not something to fear. So I wanted to address some of the big myths about GM crops you see discussed on the internet and evaluate whether there really is anything to all the anti-GM hype.

And, as with many things, the reality is more complicated than advocates for either side normally admit. As a geneticist with great interest the genetic modification of plants, I wanted to dive into some of this complexity.

For the record I am currently publicly funded and in my life I have never been funded by Monsanto/Bayer. I advocate for GM technologies and applications purely because I am interested in the topic and think that it can help, in the same way that I would advocate for reducing our carbon footprint or vaccinating, because I believe they can help the world.

So let’s look at five criticisms of genetic modification that you frequently see online:

1. “Genetic modification is completely unnatural”

Probably the most common complaint about genetically modifying a plant or animal is that it is ‘unnatural’. Part of this depends on how you define genetic modification. If you define it as any change at the genetic level, like from mutations, then that is absolutely natural it happens in every seed or baby animal relative to its parents.

Often people who advocate GM crops claim that genetic modification is completely natural because genetic changes are constantly happening in crops and livestock that we selectively breed. We have been doing this for thousands of years, and it is a normal part of all farming – organic or conventional – therefore it is natural. While this is true, I fear that this is a Strawman argument.

Most people who are concerned about this “unnatural” technology in their food are really worried about the specific methods we are using today to modify crops. So it is worth explaining what those different methods are and exactly how they work.

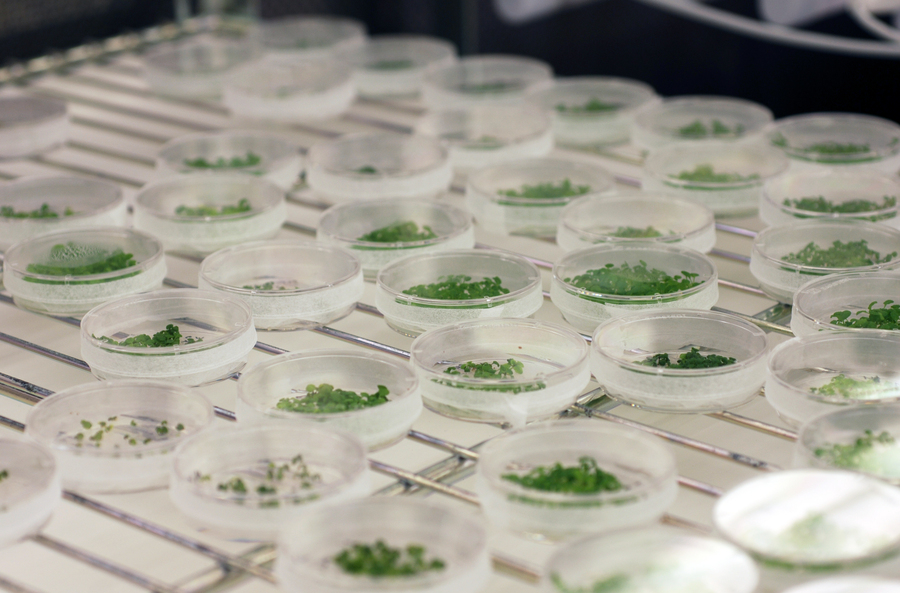

Today, the most common way to get DNA into a crop’s genome is using a species of bacteria called Agrobacterium tumefaciens (Agrobacterium for short). Agrobacterium naturally infects plants and forms tumours on their stems – you may have seen these as swollen regions on trees you walk past – creating a home for Agrobacterium to reproduce within the plant. They do this by inserting tumour-forming genes into the plant genome.

Scientists have edited the genome of Agrobacterium to remove the tumour-forming genes that allow them to infect plants, and we can replace them with other genes we want to insert instead.

The process of Agrobacterium adding genes into plants is very natural. Normally it is just an infection on a part of a plant, like a leaf or stem, but sometimes Agrobacterium can infect a reproductive cell, such as an egg cell within the flower. When this happens, all of the offspring of that plant will carry the DNA transferred from Agrobacterium. About 10,000 years ago, an insert into the genome of a sweet potato plant was captured and is present in every sweet potato you have ever eaten.

So the act of using Agrobacterium to transfer genes is actually very natural and organic. But does the act of a researcher replacing some of these bacterial genes with other, very well characterised genes, make the process unnatural?

It is true that in nature, it would be highly unlikely that a jellyfish gene would be transferred to a plant, but scientists do this routinely so that they can mark a specific part of a plant with fluorescence for research purposes. I have done this in my research to make specific cells light up under the microscope so I can better understand where genes are being turned on.

Read article in full here.